Holocaust survivor David Schaffer shared his harrowing story in a graphic novel

Published Yesterday

Holocaust survivor David Schaffer lived with humour, kindness and optimism.

The trouble started as school ended – not for everyone, but for David Schaffer. He was kicked out of public school, along with other Jewish kids in Romania under government decree in 1939. He had just started Grade 2.

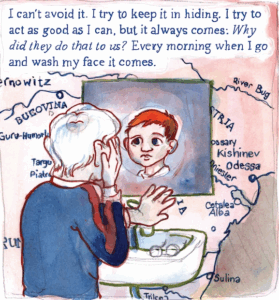

“I wasn’t expelled because I was a bad boy; being a good student and winning prizes didn’t matter then,” he recounted in A Kind of Resistance, part of the graphic novella collection But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust.

That’s when David’s real education began, with life lessons no child – no person – should have to face.

He was nine when his family was evicted from their home the following year – no Jews were allowed in rural areas. After the government deport Jews to Transnistria – part of Ukraine under Romanian occupation – they had to march, leaving behind what they couldn’t carry. For David’s family, that included his great-grandmother, who could not walk. The guards said she would be rehoused in an asylum. “The reality is we left her in the ditch near the road. She knew. That was the end of a life. One of the six million,” the book recounts.

“Being in the room with him when he said that sentence, you could see he was still feeling that pain,” recalls A Kind of Resistance author Miriam Libicki, who wrote the story using verbatim quotes from interviews with Mr. Schaffer. “He was still seeing his great-grandmother at the side of the road.”

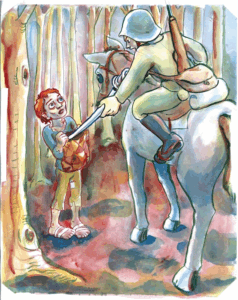

He cheated death again and again: when a Romanian soldier on horseback searching David’s bag somehow missed contraband tobacco that would have been a death sentence; when a dog belonging to other Romanian soldiers found David’s hiding spot under a barn; when typhus hit; the constant starvation.

Retrieving firewood from the forest, David tripped, dislocating his elbow. An elderly Ukrainian woman reset it. It did not heal properly and for the rest of his life, he couldn’t bend his arm all the way.

But David Schaffer got to have the rest of his life. He lived – and did so with humour, kindness and optimism. He had three sons and nine grandchildren, along with a mechanical engineering career and a cozy home in Vancouver. He also had an unlikely late-in-life third act speaking about surviving the Holocaust, educating new generations about the horrors of hate.

Mr. Schaffer is one of three survivors profiled in the book, But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust.

Mr. Schaffer died on June 12 from metastatic colon cancer. He made it – improbably, miraculously – to 94.

“He was not a person of public speaking; it was something totally new for him,” his wife, Sidi, said. “But when he let loose, it was like a river flowing. All the stories came out.”

David (Djago) Schaffer was born in the village of Vama, Bukovina in northern Romania on Feb. 27, 1931. His parents, Arnold and Dora (née Nadel) had a general store and a wholesale line of flour and sugar. His happy childhood was interrupted by antisemitic decrees and full-out war.

For more than two years, the Schaffers and another family lived in hiding among Ukrainian neighbours in what he described as peaceful co-existence. But the hunger was constant. He risked his life digging up left-behind potatoes and scooping up sugar beets that fell from farmers’ carts on bumpy roads.

“All the time, every day we were breaking the rules, and all the risks associated with that,” he told Ms. Libicki. “And that was the only way to survive.” The conversation is captured in Chorong Kim’s short film If We Had Followed the Rules, I Wouldn’t Be Here.

Liberated by the Russians in March, 1944, David and his parents tried to return on foot to their home, but could only get as far as Mihaileni, about 100 kilometres away.

By that point, he had forgotten most of his reading and writing. His parents homeschooled him until an “elementary school for the evacuated” opened. He was 13; his parents registered him in Grade 4. He was quickly moved up to Grade 5 and continued to excel until Grade 9, when the school closed.

Mr. Schaffer had three sons and nine grandchildren, along with a mechanical engineering career and a cozy home in Vancouver.

He began working with his father, loading and unloading railway cars by hand. He apprenticed as a blacksmith. But he never gave up on his education, finally completing high school at the age of 23.

He studied engineering at the Polytechnic Institute of Bucharest – but was expelled shortly before writing his final exam on Christmas Eve, 1959. No reason was offered, but he assumed it was because his family had applied to immigrate to Israel.

At a New Year’s Eve party on the cusp of 1957, he met Sidi Spiegel. Taller than average, Sidi, 18, had agreed to go to the party only if there would be tall boys there. David, 26, was tall – and funny. “As soon as David came in, we started to dance,” recalls Sidi. They danced “the whole night.”

After four years of long-distance dating – Sidi’s family had moved to Israel – David moved there as well in 1963. A few months later, they married.

In Israel, David finally received his engineering degree. He and Sidi had three sons – Nathan, Doron and Ayal.

At their 60th-anniversary party, their grandchildren – today aged 14 to 26 – read excerpts from the trove of love letters and postcards they had exchanged during their long-distance years.

In 1975, visiting Edmonton for a family bar mitzvah, Mr. Schaffer was offered an engineering job and accepted. There were subsequent moves to St. John, Quebec City and Victoria, where he worked in shipbuilding.

He emphasized the importance of education to his children. One son became an engineer, the other two, psychiatrists.

David and Sidi retired in Vancouver, but retirement didn’t stick. In the 1980s, he worked for two years as an engineer on the city’s new SkyTrain system.

In Vancouver, David and Sidi joined a group of child survivors of the Holocaust, who met at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) monthly. The group became like family.

The private person whose formal education was cut short repeatedly and “didn’t want to burden us with his emotional baggage and history,” says Ayal, opened up in his late 70s and 80s, not just to his family, but with a nascent project created by University of Victoria professor Charlotte Schallié that became But I Live.

Ms. Libicki, who is based in the Vancouver area, was impressed with Mr. Schaffer’s vivid memory and precision. Sometimes the drawings weren’t quite right, as in her depiction of a fireplace. When he wasn’t satisfied with her attempts, he drew an alternate.

“He was not an artist, but he was an engineer,” Ms. Libicki says. He also had a good sense of humour. “He would just come out with a little joke or one-liner when you were not expecting it.”

The photos he showed Ms. Libicki were all black and white, so she did not realize for some time that he had red hair as a child (his hair, by this point, was white). When she learned that, she created a special orange tint specifically for his hair, so he could easily be distinguished in a scene.

Mr. Schaffer was thrilled that the book was translated into German and distributed to schools in the country.

As the book launched, Mr. Schaffer found himself in the spotlight.

“Once the book came out and we started to do events together, I could see that it really lit him up,” says Ms. Libicki, who adds that he was meticulous, often speaking with piles of notes. “And when he saw how touched and moved people were from listening to him, you could see it was very, very gratifying to him.”

He was thrilled to see the book win awards and recognition. But most important was its role in education. He was so proud that an educational curriculum was developed alongside it, in partnership with UBC.

Despite being ill, Mr. Schaffer was able to participate this past April in a commemoration of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, at the VHEC. The premier was there as was MLA Jessie Sunner, parliamentary secretary for anti-racism initiatives. As she was leaving, Mr. Schaffer called her over and handed her a copy of the book. He had signed it. “Cherish freedom,” he wrote.

He was thrilled that the book was translated into German and is being distributed to schools in Germany. About a month before he died, he learned that an exhibition featuring panels from the book would be installed at the Bergen-Belsen Memorial this spring. “This was his last present,” Sidi says.

His goal with this project was always to educate the public – not just about what happened to him, but what could happen in the world, still. As he wrote in But I Live: “Through reading my story, I hope to inspire you to be alert, learn from history, and take action when necessary to protect our freedom and way of life.”

Read our member Jan Lee’s article at the JNS on May, 11 2024.

The resounding importance of Yom Hazikaron

Israel’s Day of Remembrance has significance for us all, even Diaspora Jews.

An Israeli soldier places flags around the Mount Herzl Military Cemetery in Jerusalem ahead of Yom Hazikaron, May 8, 2024. Photo by Yonatan Sindel/Flash90.

This year, more than most, Jews internationally need to commemorate Yom Hazikaron.

Israel’s Day of Remembrance was created more than 70 years ago with a unique purpose, which was to honor soldiers and civilian fighters killed during the efforts to establish its nationhood. But in recent years, it has taken on an additional role: to acknowledge the mounting numbers of citizens murdered during terrorist attacks on Israeli soil.

But this year’s memorial has another, often overlooked significance. This year marks a half-century since the terrorist attack in the northern city of Kiryat Shmona when 18 civilians, largely immigrants, were murdered in their homes. Eight of the victims were children in their apartments during the Passover holidays. The massacre and the terror attacks that followed during the next few months that year became front-page news in international media, forcing the U.N. Security Council to intervene and call for a buffer zone on Lebanon’s southern border. According to U.N. Security Council records from April 1974, Israel’s efforts to persuade the United Nations to hold both Lebanon and the Palestinian Liberation Organization accountable for the cross-border attack were rebuffed. U.N. peacekeeping troops were established briefly on the border, but Lebanon refused to assume responsibility to stop terrorists from crossing into Israel.

I was in Kiryat Shmona a half-hour before the attack that morning. I was waiting for a bus to Jerusalem, where I planned to spend the rest of the Passover holiday. The bus left filled with travelers, including residents from the apartment building that had been targeted. Egged buses in those days were equipped with a portable radio that in the best of times was hard to hear over the chatter of riders. But when the emergency broadcast came on, panic ensued. Passengers began pleading with the driver to turn the bus around and head back to Kiryat Shmona so they could check on their families. The bus was eventually flagged and pulled over by a supervisor, who confirmed the news. The city had already been cordoned off by Israel Defense Forces, and the driver was ordered to continue on to Jerusalem.

It was a searing experience to step off a bus crammed with families and solitary travelers, knowing that some had survived a terrorist attack because they were on a shopping trip instead of at home. And worse, that they might not find out the fate of their families until they returned home. But the image I think of every Yom Hazikaron is that of the young Russian immigrant from Kiryat Shmona sitting next to me, whose tears were reflected in the window pane next to her. She had confessed to me a few minutes earlier that she was still learning conversational Hebrew. Apparently, she knew enough to understand the worst of the news broadcast.

Public memorials like Hazikaron help us heal. But they also serve as a way to register and reflect public unity and sentiment about compelling issues. And sometimes, when our representatives listen hard enough, response to those memorials can inspire action.

Perhaps Israel’s decision last year to enact a policy that recognizes the worldwide victims of antisemitism was prescient of the increasing need for global action against terrorism. It’s an uncomfortable thought. But if Israel is going to overcome the greatest threat to its safety, it won’t just come from within—from the yearly sirens that mark its losses or from its incessant efforts to inspire the United Nations to finally support its side of disputes. It will also come from those of us in the Diaspora, who know all too well the importance of a Jewish homeland.